One of the most common ways to produce light today is with a light-emitting diode (LED). LEDs are popular because they consume little power, resist impact, and last a long time, which is why they appear in many shapes and products. To understand why an LED emits light, it helps to start with how a standard diode works—because in theory, it can also emit light, just very inefficiently and often in a way we can’t easily see.

1. What a Diode Does: Current in Only One Direction

In a simple circuit with a lamp and a power source, current flows easily because electrons move freely inside metal conductors. But when you place a diode in the circuit, the current may either pass or be blocked depending on how the diode is oriented.

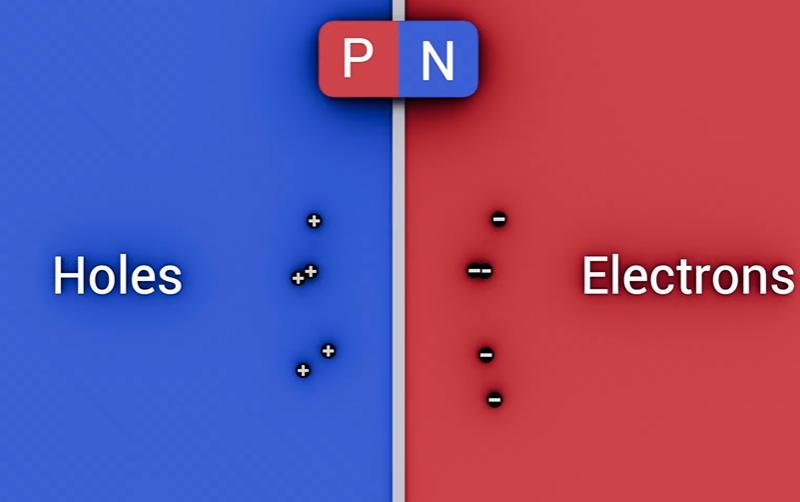

This one-way behavior comes from the diode’s internal structure. A diode is made from semiconductor material (commonly silicon) that is formed into two different regions: N-type semiconductor and P-type semiconductor. Where these two regions meet, they form a PN junction, which is the heart of diode behavior.

2. Why Semiconductors Are Special: Doping Changes Conductivity

Pure silicon is not a great conductor

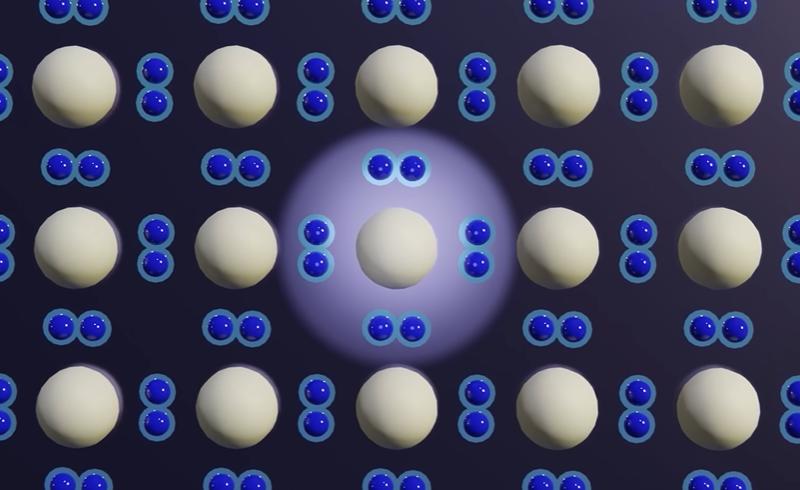

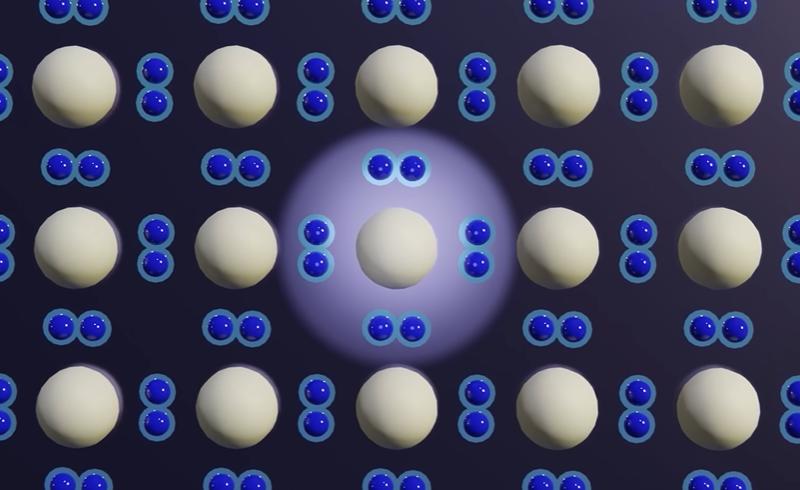

In pure silicon, each atom has four valence electrons that are shared with neighboring atoms in a crystal structure. This sharing creates very stable bonds, and because the electrons are tightly “held” in the structure, silicon does not allow electrons to move freely like a metal does.

Doping: adding impurities to control electron movement

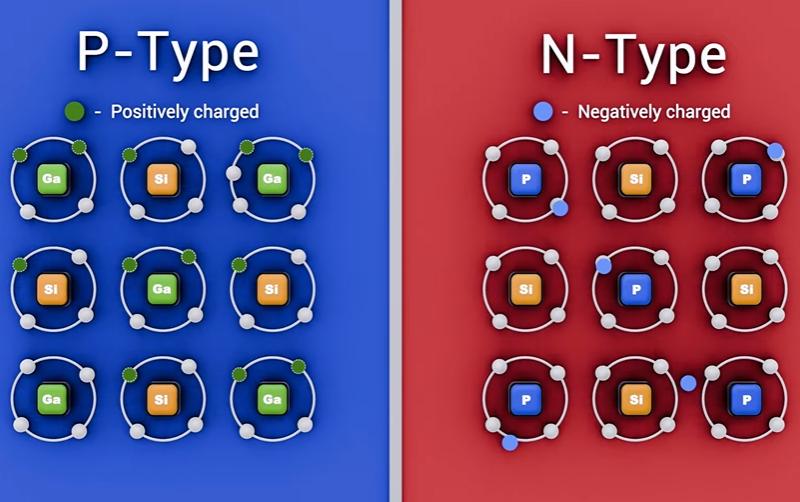

To make silicon useful for electronics, engineers use doping, which means adding tiny amounts of other atoms to change silicon’s electrical properties:

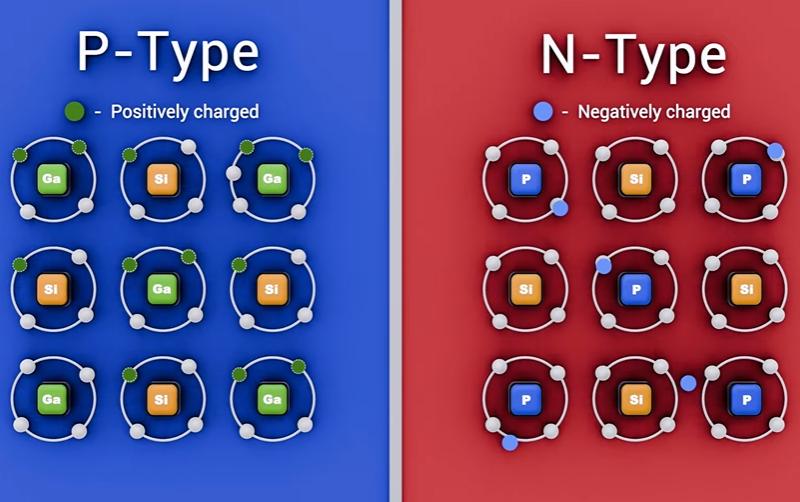

N-type (negative): Add atoms with five valence electrons.

One electron becomes “extra” and can move more easily, creating a material rich in free electrons.

P-type (positive): Add atoms with three valence electrons.

This creates a missing electron, called a hole. Holes behave like positive charge carriers and can “move” through the material as electrons shift to fill them.

3. Forward Bias vs. Reverse Bias

Depending on how voltage is applied, two main cases occur:

Reverse bias (blocks current)

If the power source is connected so that the charge carriers are pulled away from the junction, electrons and holes move in directions that prevent conduction. In this condition, the diode effectively stops current.

Forward bias (allows current)

If the polarity is reversed, electrons in the N-type region are pushed toward the junction and can cross into the P-type region. Holes also move toward the junction from the other side. The circuit becomes conductive, and current flows.

This forward-bias condition is also where the light-emission process happens in an LED.

4. What Is an LED?

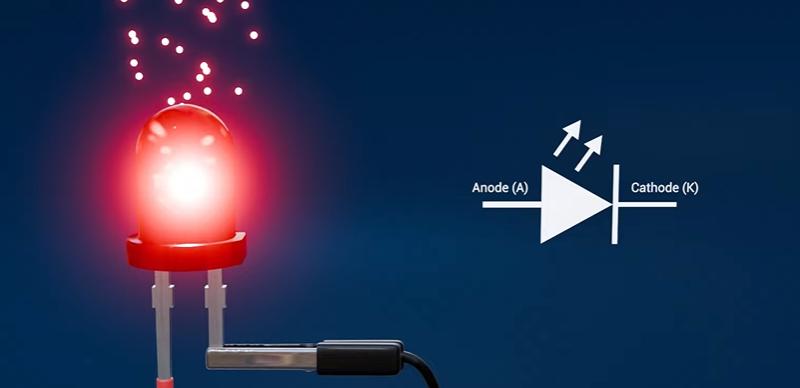

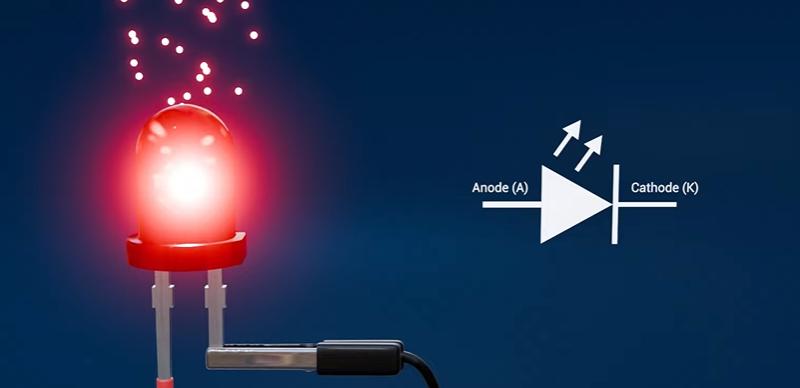

An LED (Light Emitting Diode) is a tiny two-terminal semiconductor device that emits light when current flows through it in the correct direction. Unlike a resistor or incandescent bulb, an LED won’t significantly conduct or glow until the applied voltage exceeds its forward voltage threshold. Once that threshold is reached, the semiconductor junction releases energy as photons—light.

Like all diodes, it has two terminals:

Anode (A): the positive terminal where conventional current enters

Cathode (K): the negative terminal where conventional current exits

The LED symbol looks like a diode symbol with two outward arrows indicating emitted light. Visible LEDs typically emit within roughly 380–740 nm.

5. The Core: PN Junction and Threshold Voltage

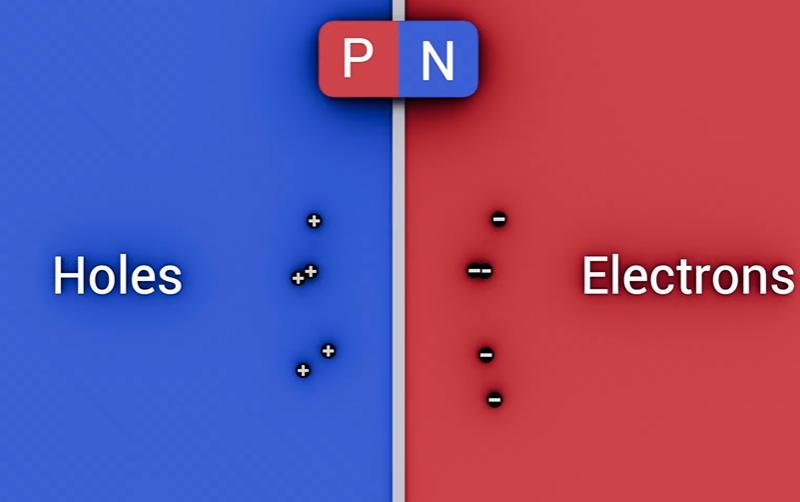

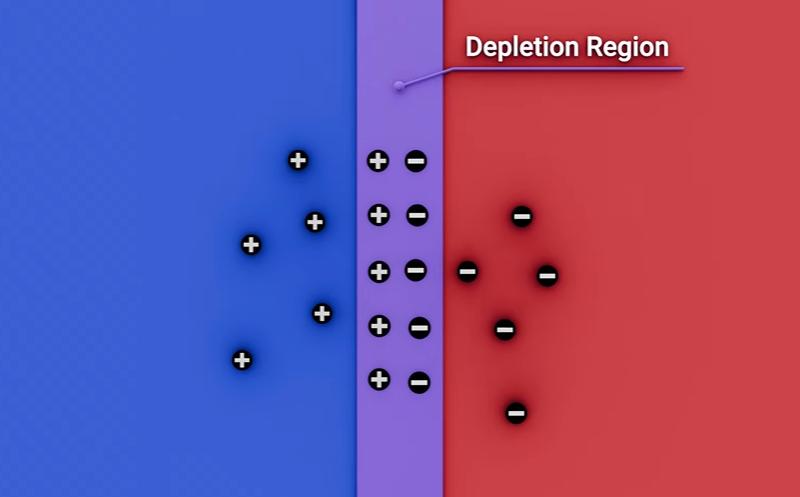

When P-type and N-type semiconductors touch, the boundary is the PN junction.

At its core, an LED is a PN junction made from a direct band-gap semiconductor with two differently doped regions:

The P-side contains holes (positive charge carriers) and sits near the anode.

The N-side contains free electrons (negative charge carriers) and sits near the cathode.

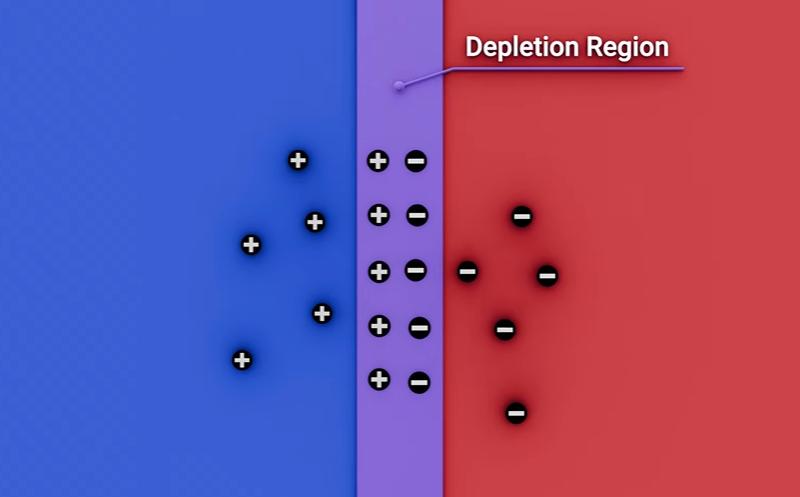

When the PN junction forms, electrons and holes recombine near the interface, creating a depletion region (a zone depleted of free charge). This region acts as a barrier. The LED only conducts strongly—and emits light—once the applied voltage is high enough to overcome that barrier, which is why LEDs have a forward voltage threshold.

6. Electroluminescence: Photon Emission by Recombination

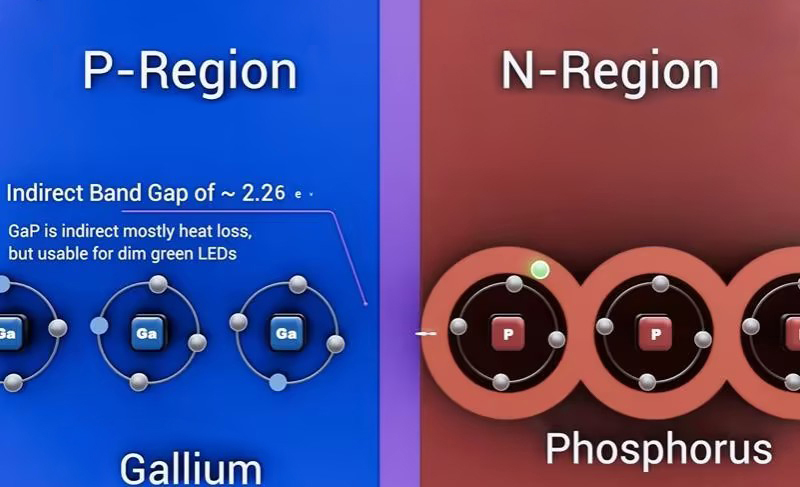

Under forward bias, electrons from the N-side are injected into the P-side and recombine with holes in the active region. During recombination, electrons drop from a higher-energy state to a lower-energy state, releasing energy in the form of photons. This light-generation mechanism is known as electroluminescence.

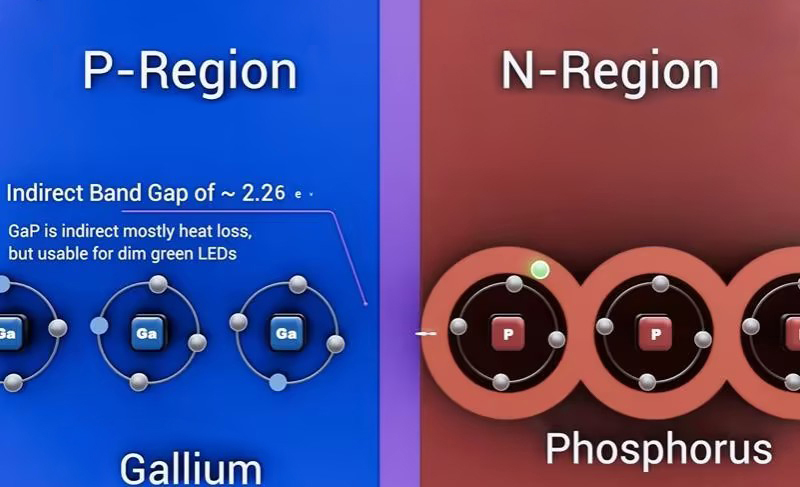

Material choice strongly affects efficiency: Direct band-gap materials favor radiative recombination (photon emission), making them ideal for LEDs, while indirect band-gap materials typically dissipate energy non-radiatively as heat, leading to much lower light-emission efficiency

7. Band Structure and Band Gap: Why Color Changes

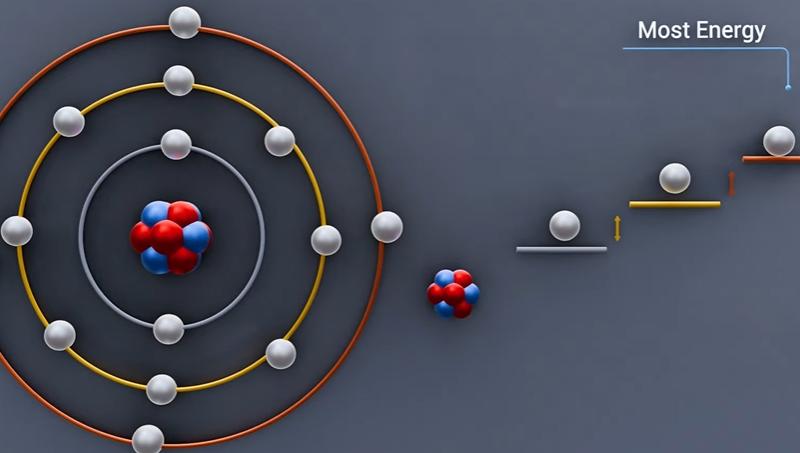

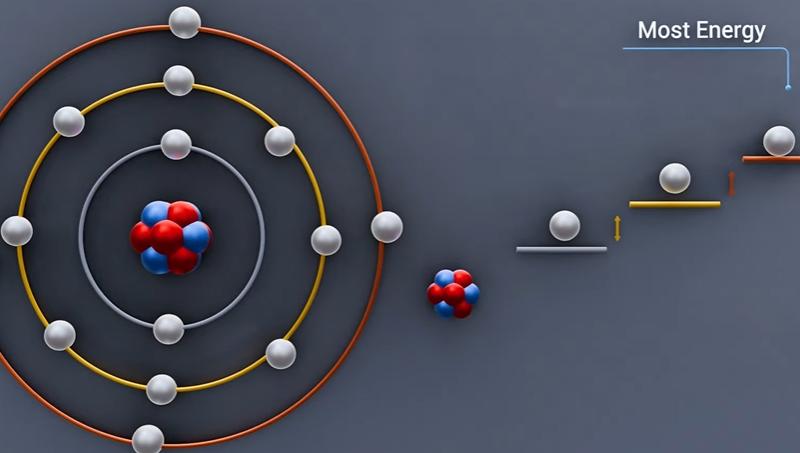

Semiconductor energy states are commonly described using the valence band and conduction band:

Valence band: lower-energy, more tightly bound states

Conduction band: higher-energy states that support free carrier motion

The energy difference between them is the band gap.

In direct band-gap materials, recombination releases energy close to the band-gap value as photons. A larger band gap produces higher-energy photons (shorter wavelengths), while a smaller band gap produces longer wavelengths. By engineering semiconductor alloys, manufacturers can produce LEDs across the visible range and even into infrared and ultraviolet wavelengths.

Wrap-up

LEDs translate semiconductor physics into practical light output, offering high efficiency and strong reliability for modern lighting and display systems. From industrial equipment and vehicles to consumer electronics, LEDs continue to advance how we generate and control light.

If you want more information about LED lights, welcome to our website www.ogaled.com and immerse yourself in the sea of knowledge!